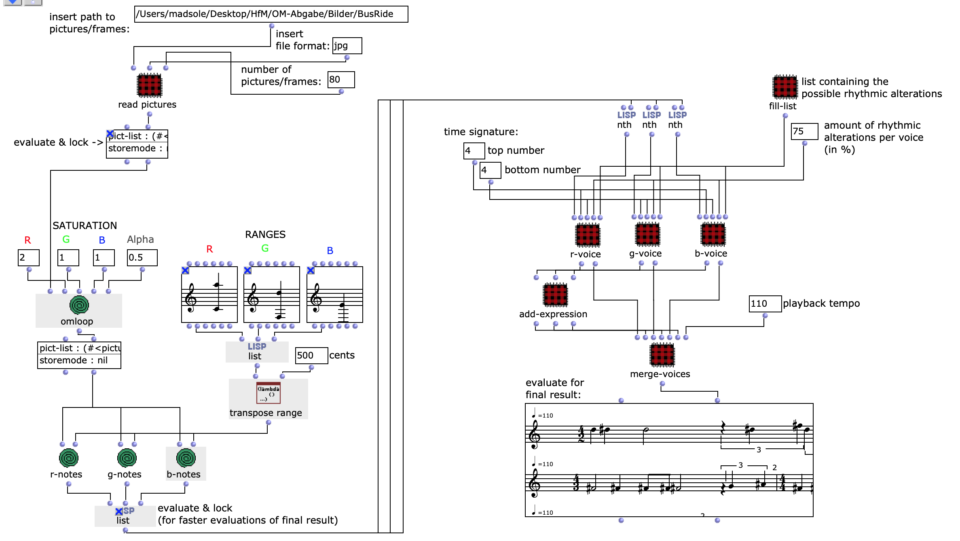

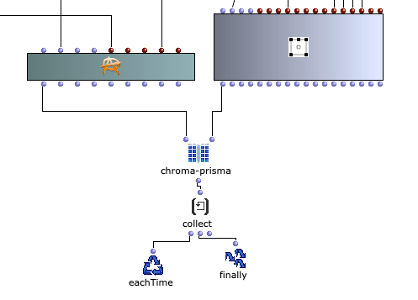

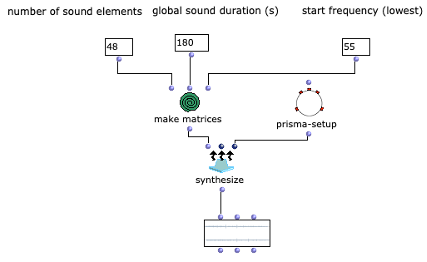

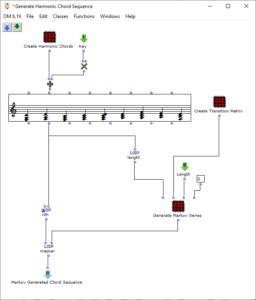

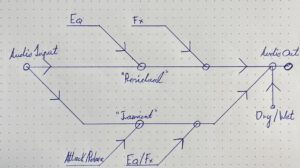

Abstract: This project deals with the design of an OpenMusic application that has the goal of converting image sequences into a symbolic music representation consisting of three voices.

Responsible: Mads Clasen

Source material and preparation

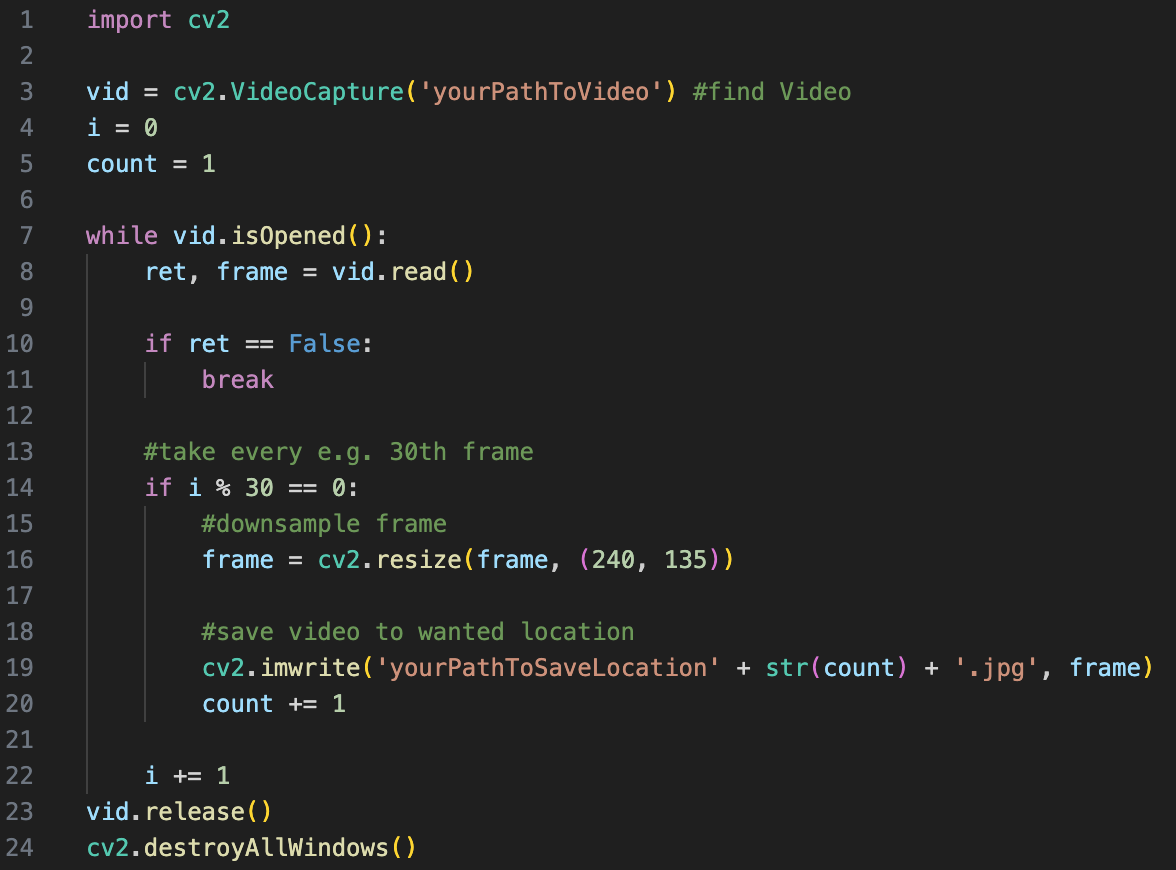

The image sequence can be individual frames from a video, a series of images from an artist or images you have compiled yourself. These must first be available in a folder on the relevant computer. If it is a video, it must first be broken down into its frames outside of OpenMusic. In Python, this can be done very easily in just a few lines with the help of the OpenCV library.

Fig. 1: Splitting video in Python

As can be seen in the code example, the resulting images should also be named numerically with numbers from 1 to n and, depending on the computing power of the computer and the number of images, be downsampled. This, as well as the installation of the Pixels Library in OpenMusic itself, is necessary for the patch to work properly.

Sonification

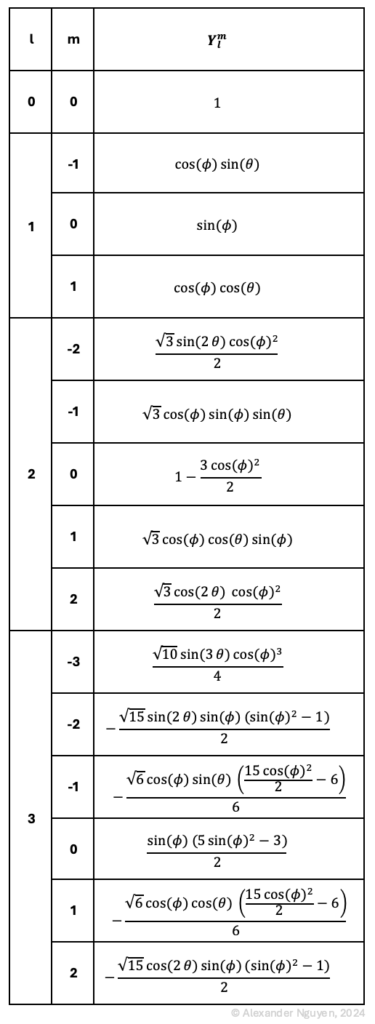

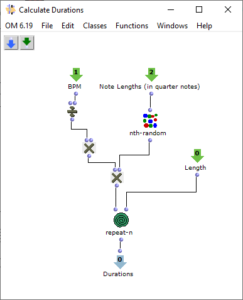

Note values

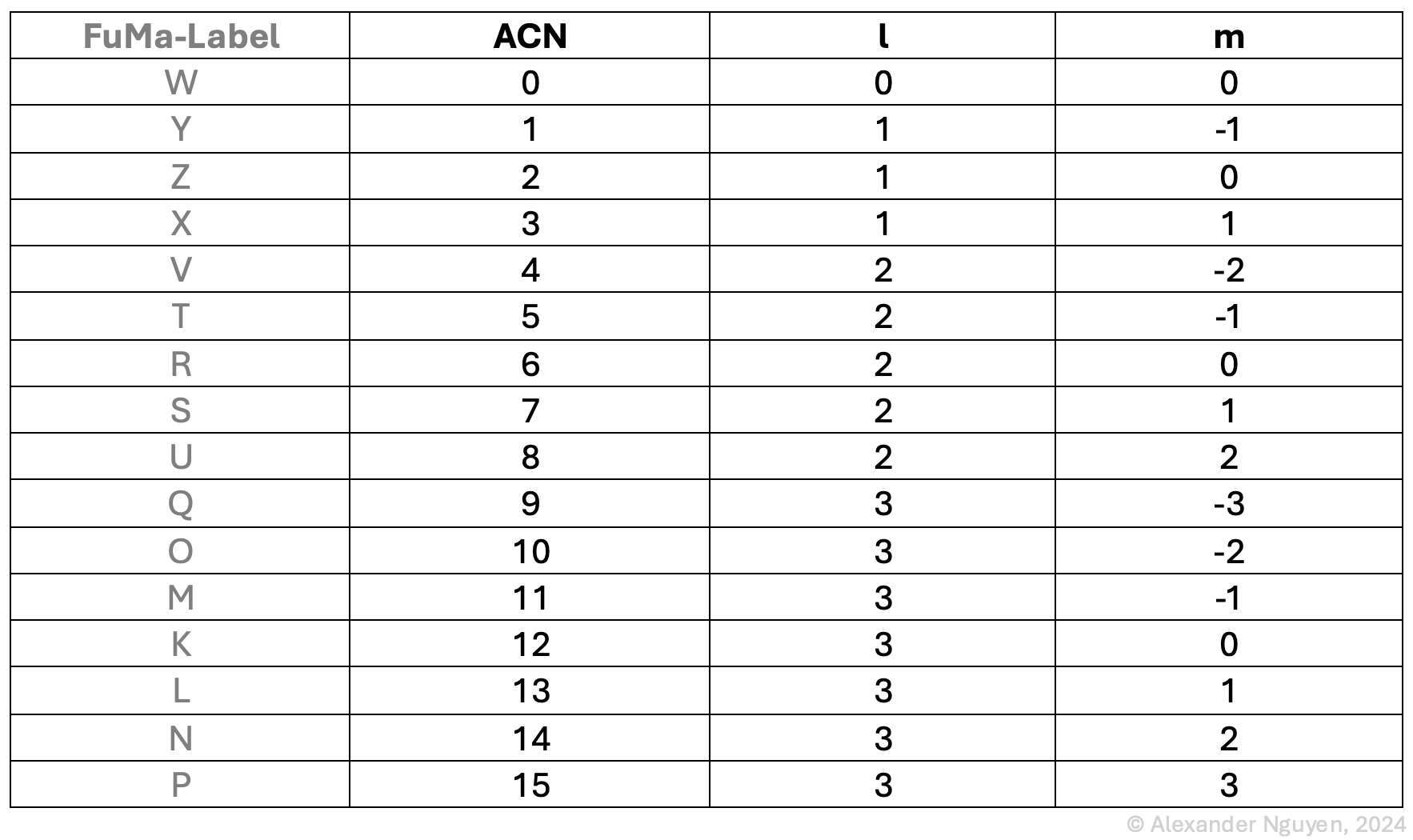

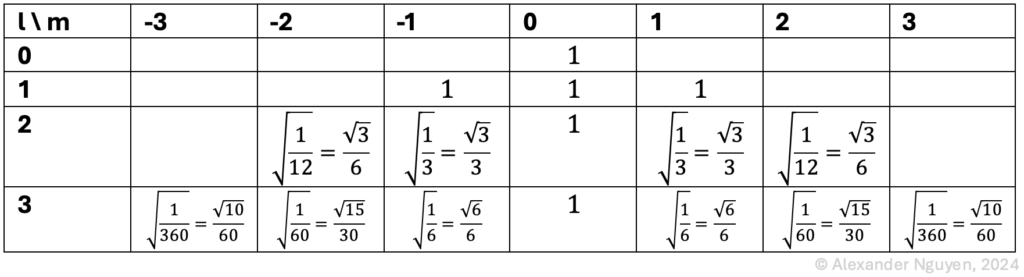

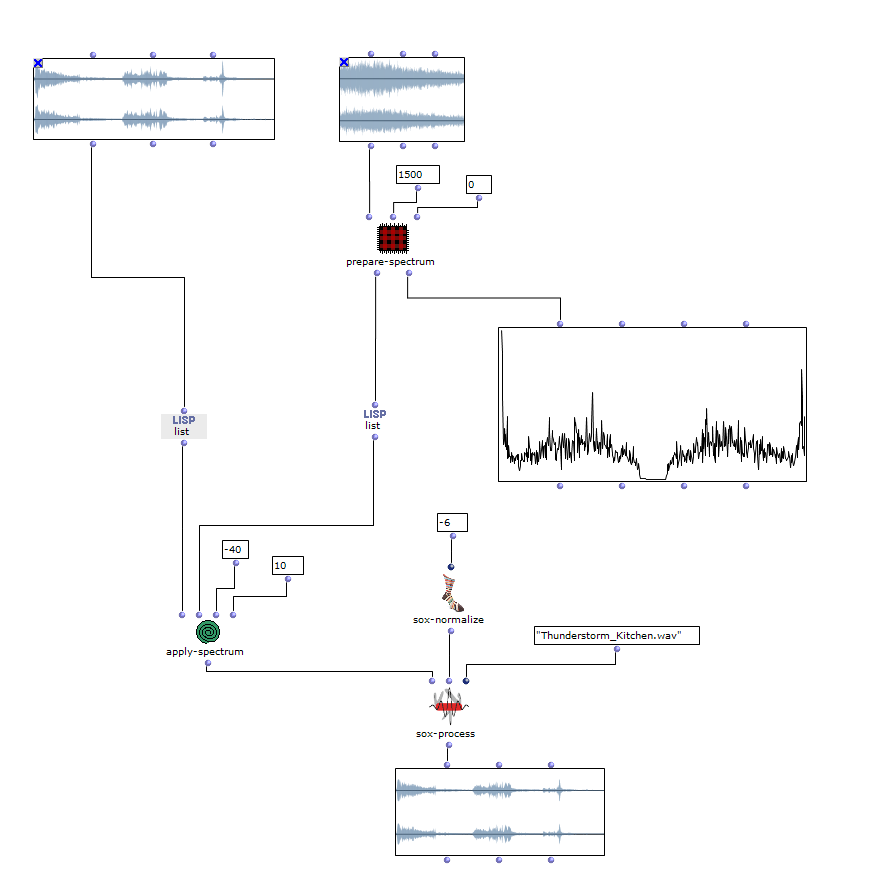

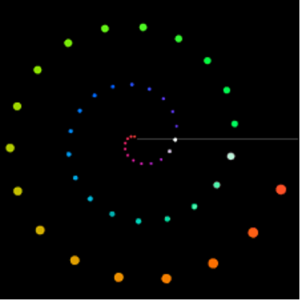

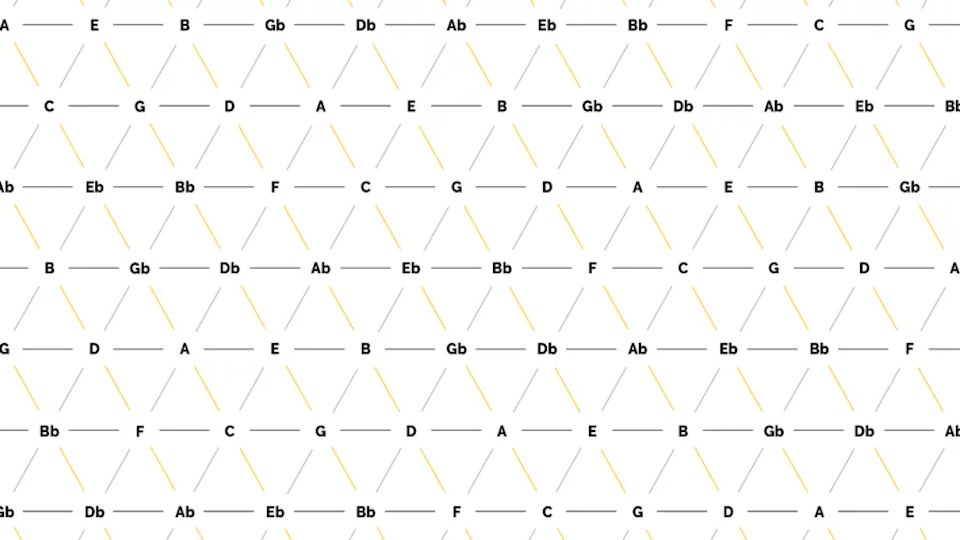

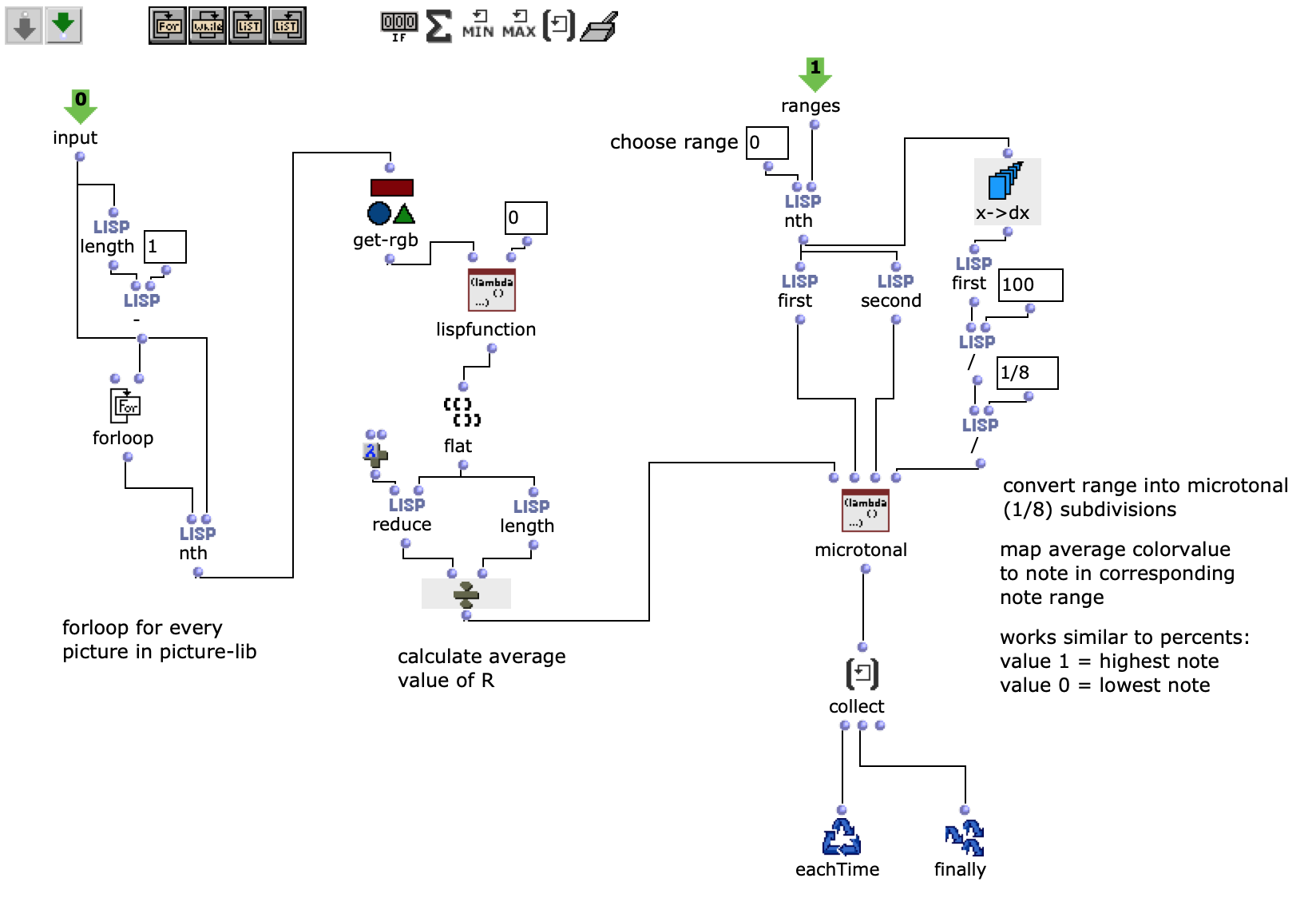

After specifying the file path, file format and number of images, the desired images are loaded into a picture-lib object and summarised as a list. The average R, G and B colour value is read from each image in this list and mapped to a corresponding note. In this case, the R, G and B values are treated as different voices and each have their own note range within which they move. This range is additionally subdivided into microtonal steps (1/8 notes) to which the values are finally mapped. A value of 1 corresponds to the highest possible note and 0 to the lowest. Accordingly, one note for each of the three voices is read from an image.

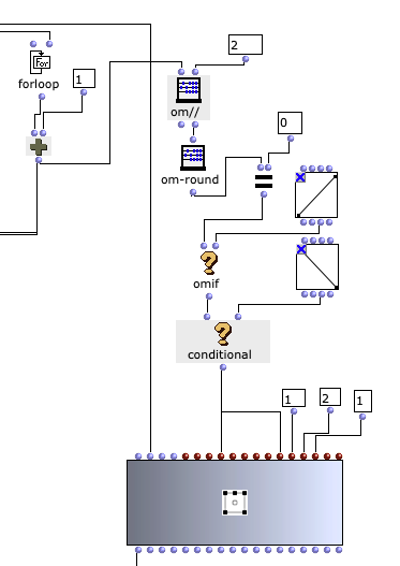

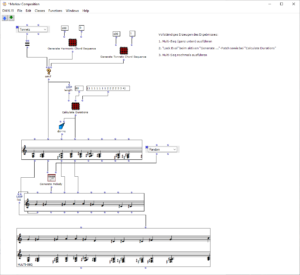

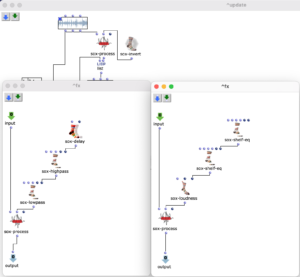

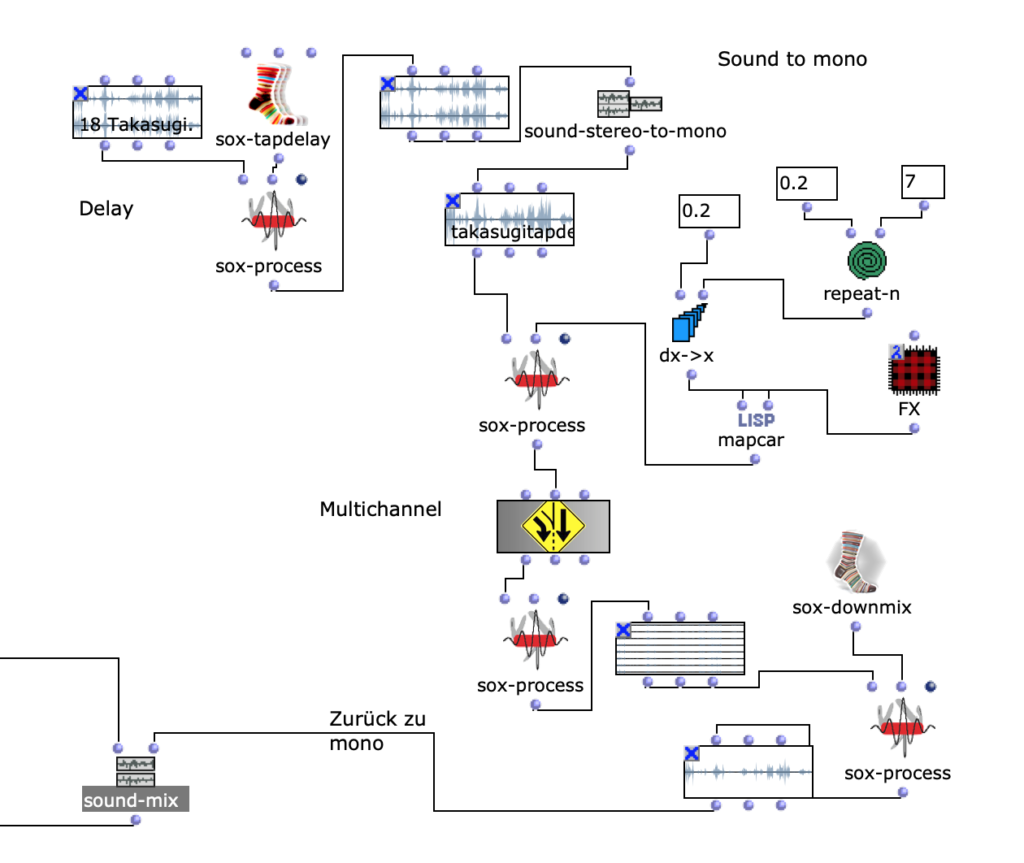

Fig. 2: Generation of a score line

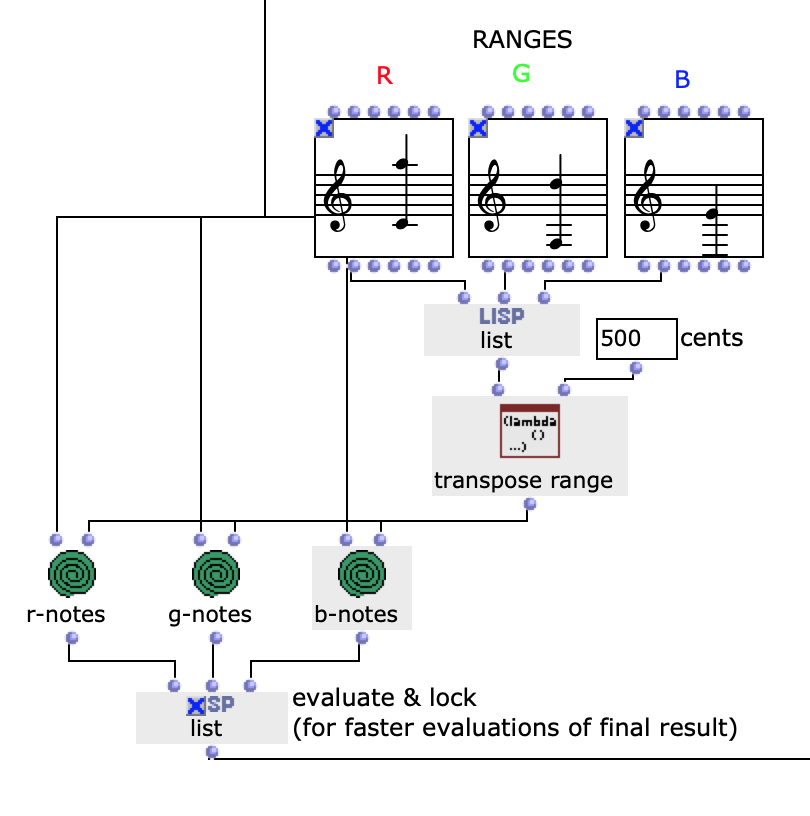

The note ranges in which the colour values move can be adjusted using the corresponding chord objects; it is also possible to transpose all ranks uniformly by a desired value in midicents. The preset values correspond to the approximate note ranges of soprano (R), alto (G) and bass (B) voices. After running through the entire image sequence, there are now three voices with a number of notes corresponding to the number of images entered. These voices are processed independently of each other in the next step.

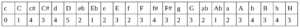

Fig. 3: Mapping the RGB values onto note values

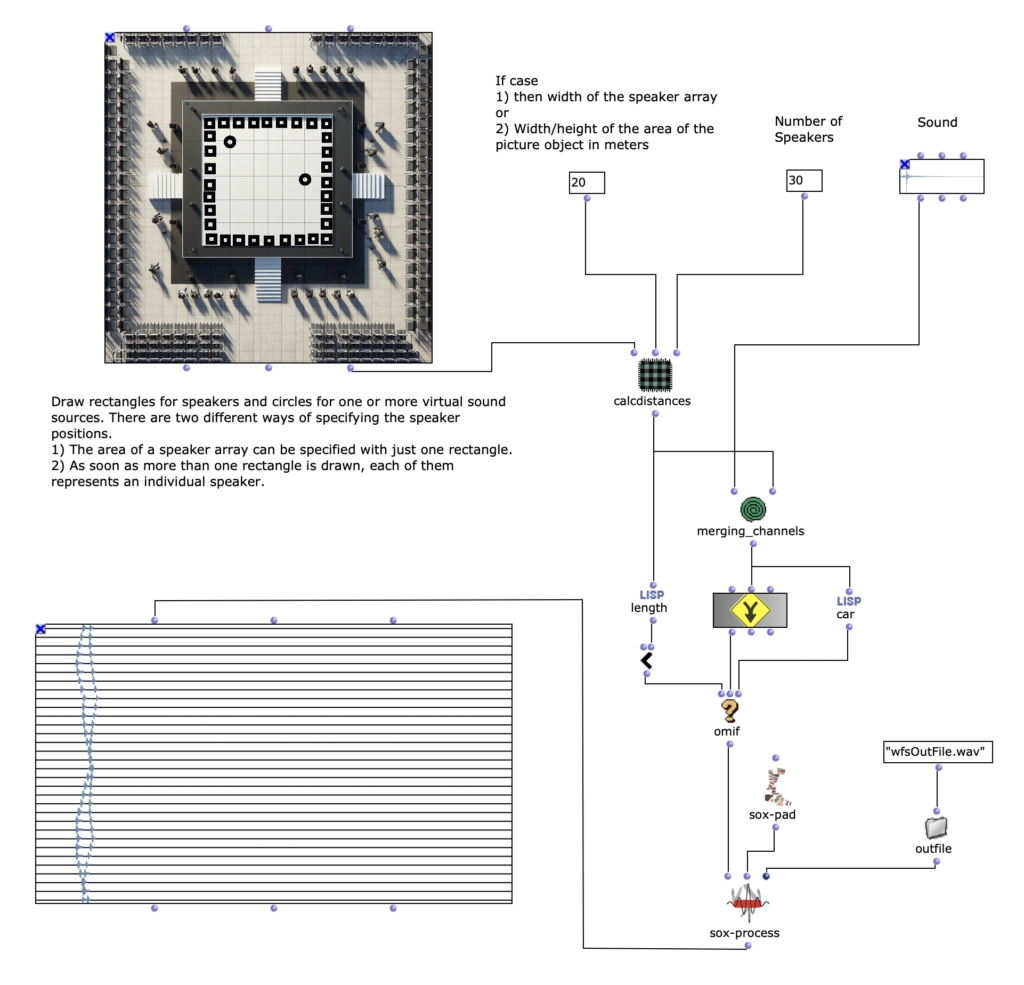

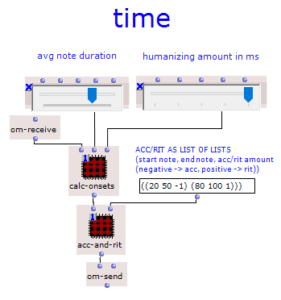

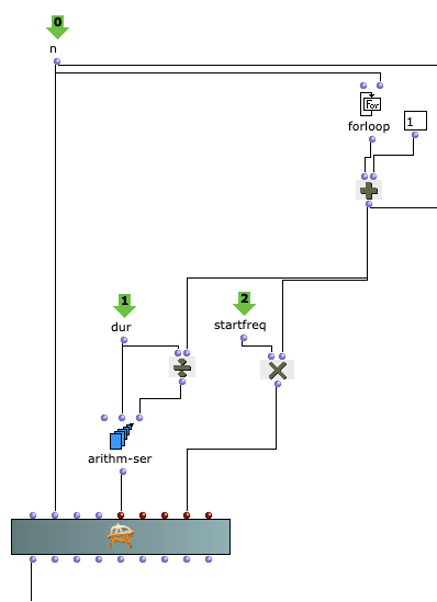

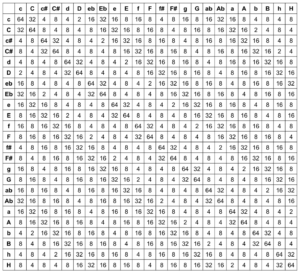

Rhythm

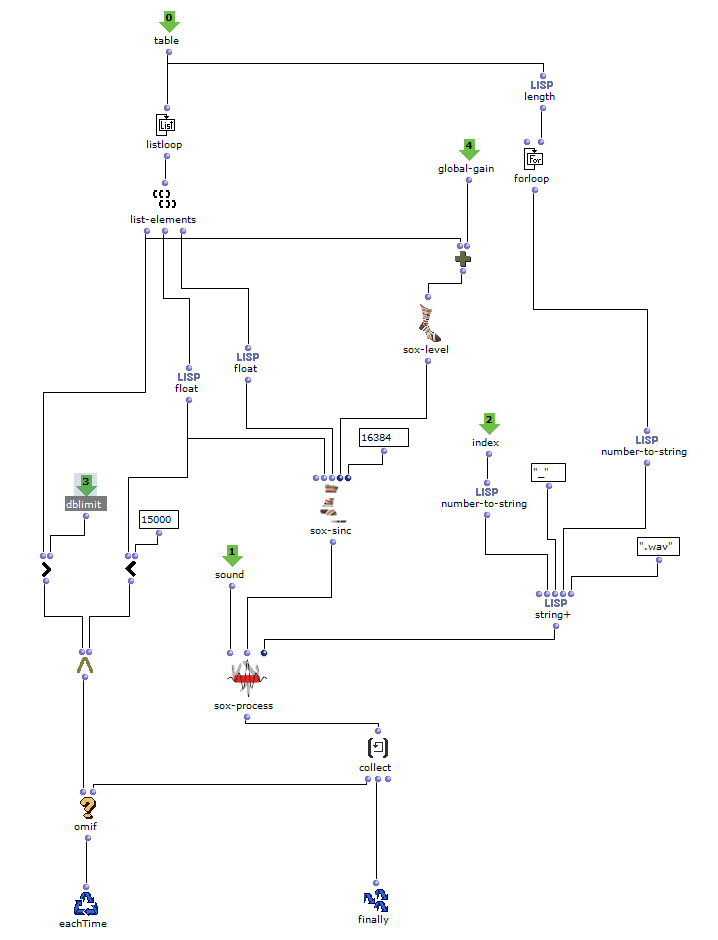

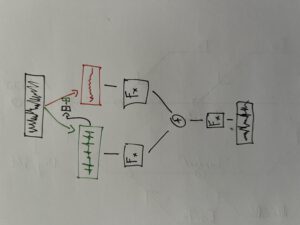

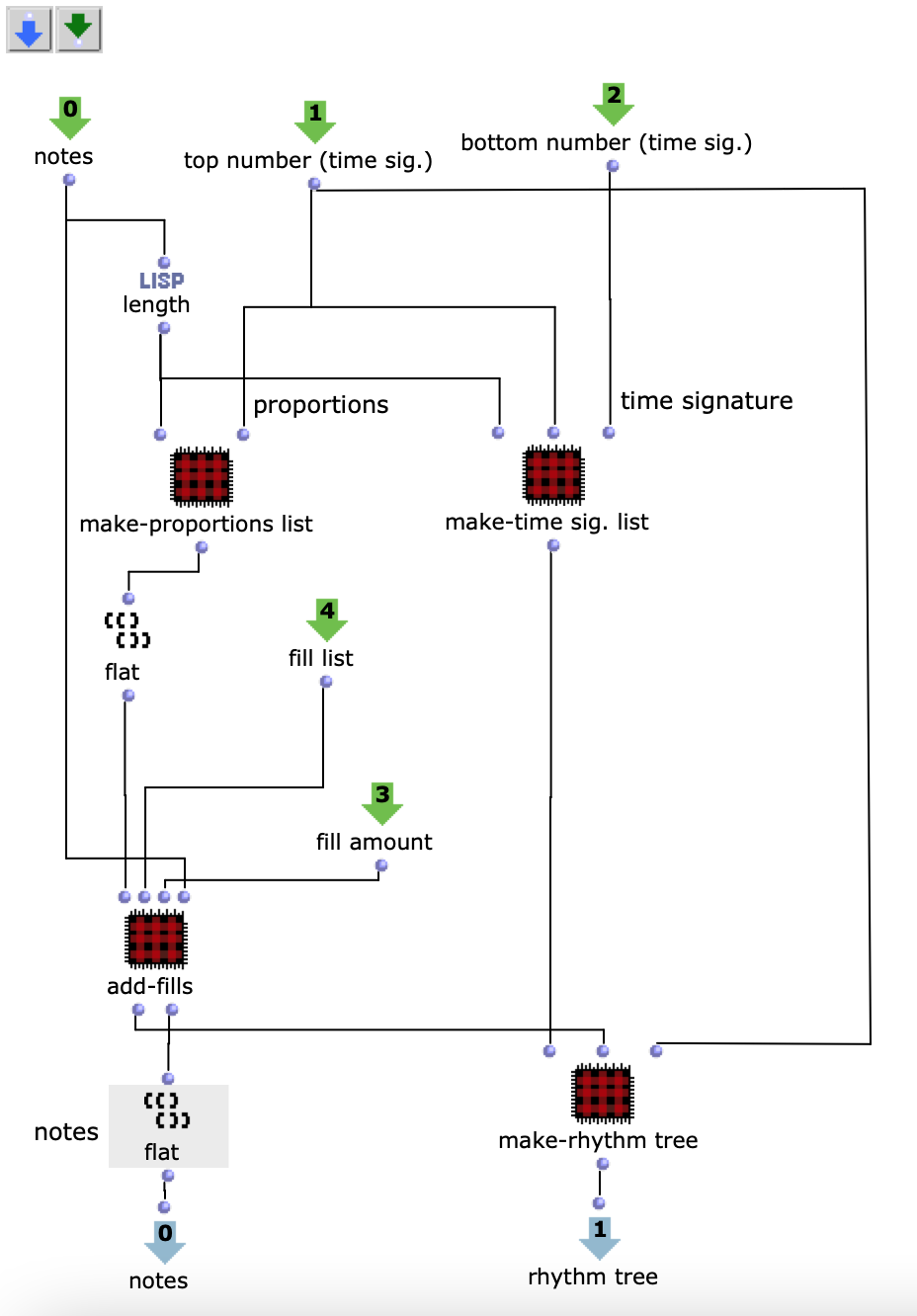

As I have decided to use voice objects because of the direct way of influencing rhythm, the rhythm trees required for this are created first. Or rather the two building blocks of a rhythm tree : time signature and proportions. A list is created for each of these, based on the number of notes and the time signature, which are later merged into the required rhythm tree form using a simple mat-trans object.

Fig. 4: Generating the rhythm tree

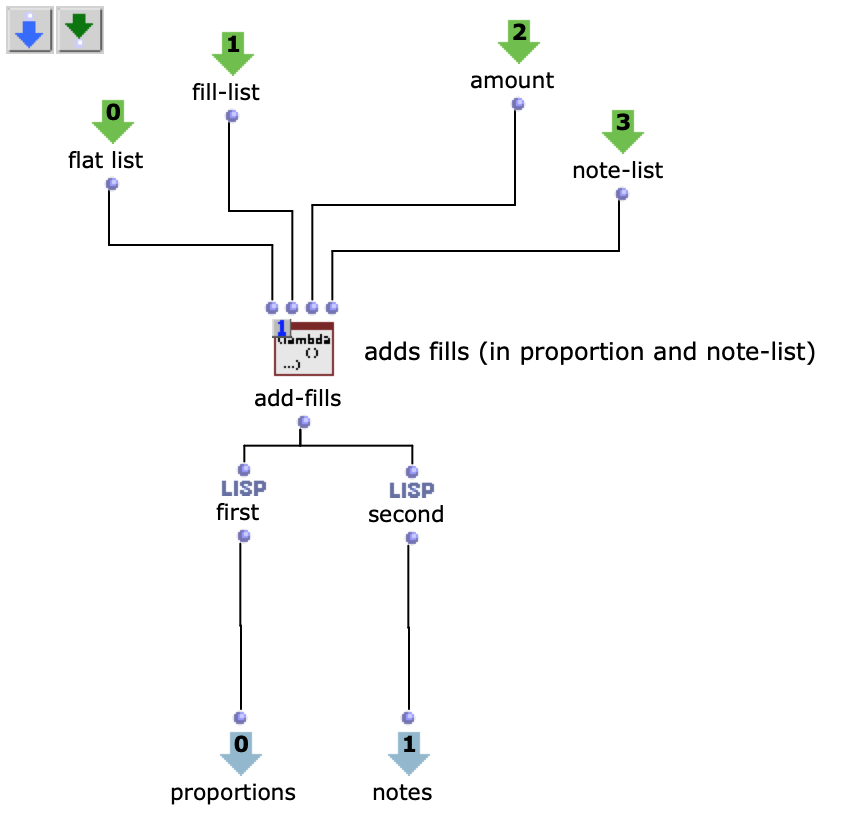

Before this, however, the list responsible for the proportions is enriched with ostinato. For this purpose, there is a second list containing various possibilities for such ostinato, from which one is selected at random and placed in a random position in the proportion list. As this increases the number of note values, new notes corresponding to the embellishment are inserted at the same position in the list containing the notes. Starting from the original note, a decision is made between constant, ascending or descending notes. The strength with which these ornaments are to be included in the parts can also be adjusted.

Fig. 5: Addition of rhythmic ornaments

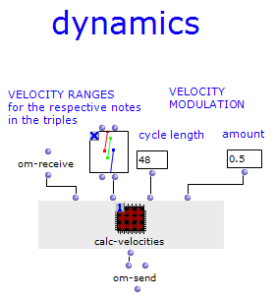

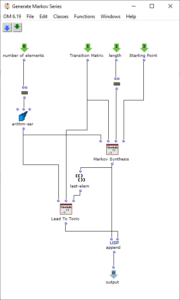

Dynamics

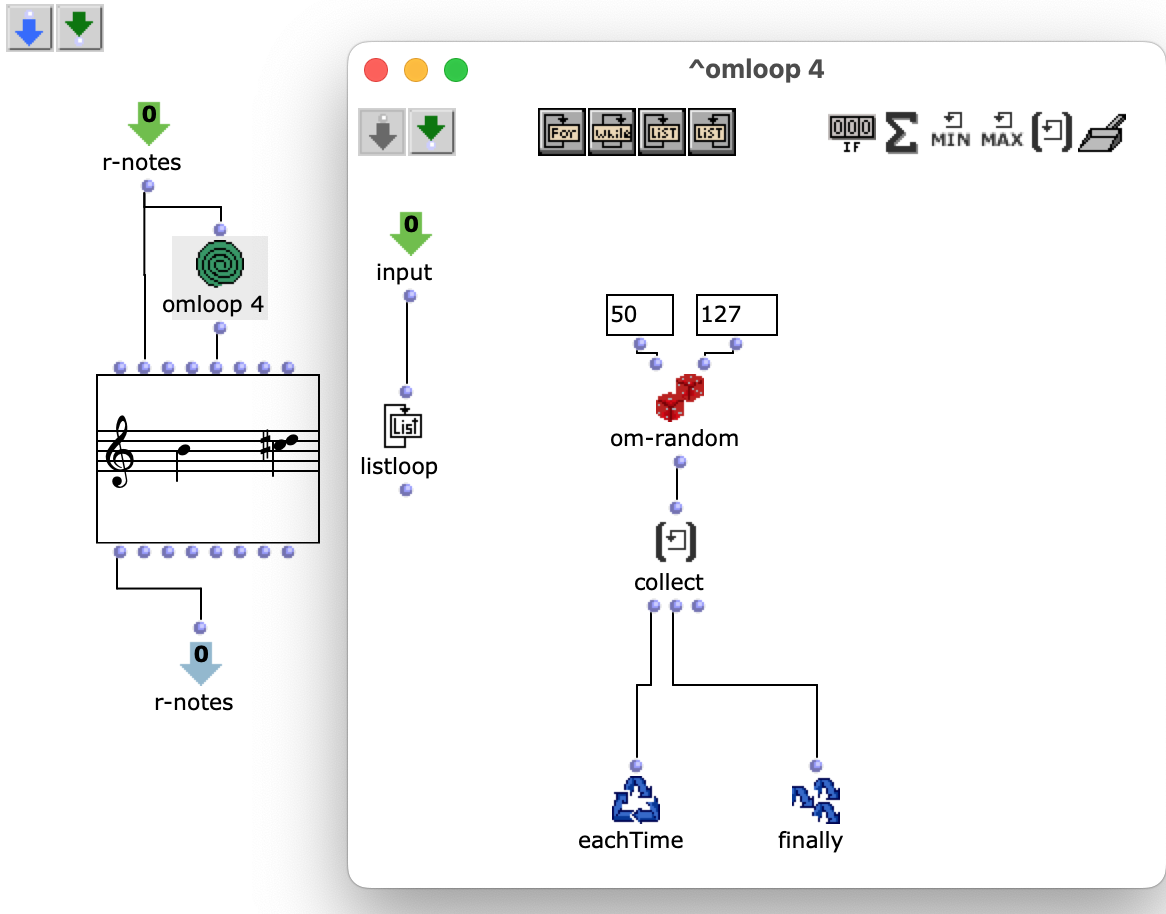

The edited proportions are then merged with the list that determines the time signature to form the rhythm tree . The corresponding note list goes through one more step, in which a random velocity value is assigned to each note.

Fig. 6: Creating dynamics

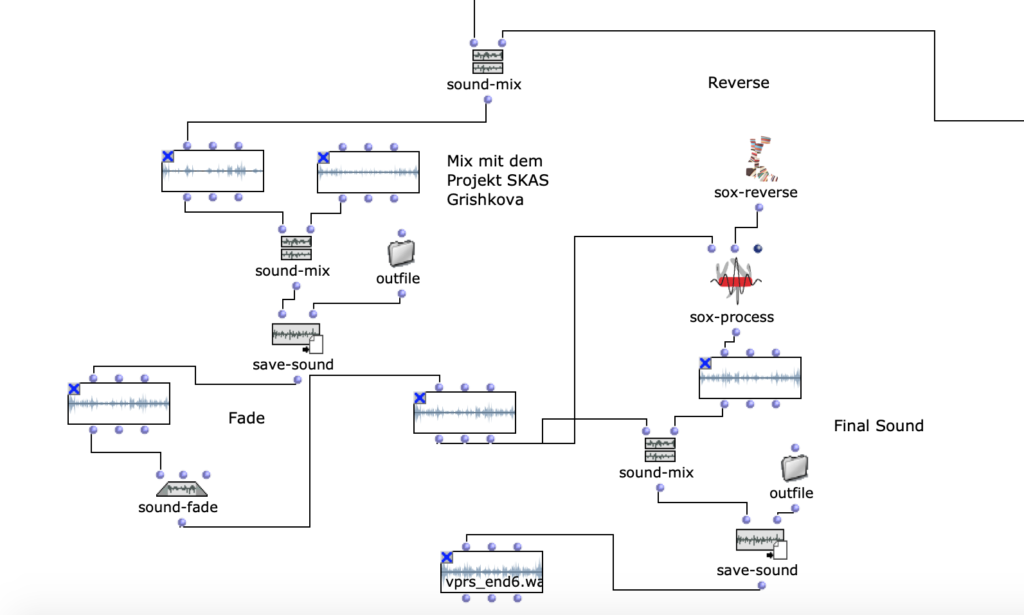

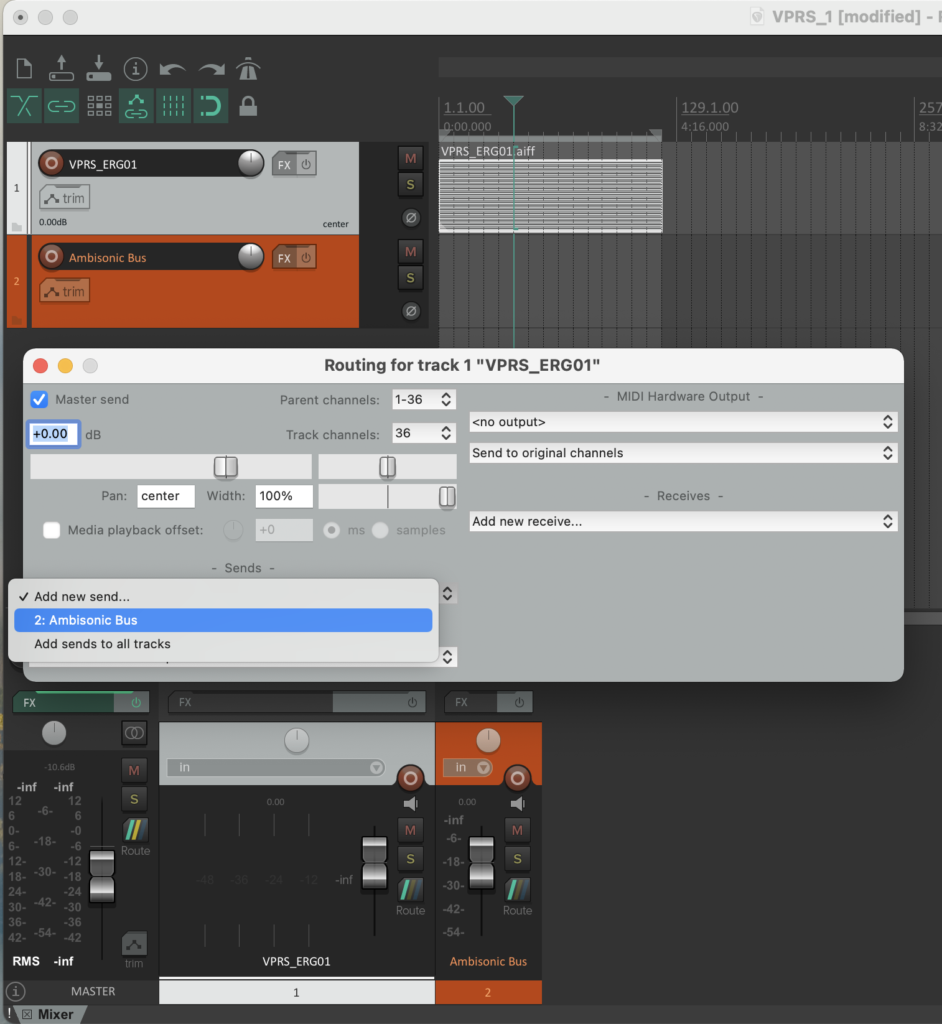

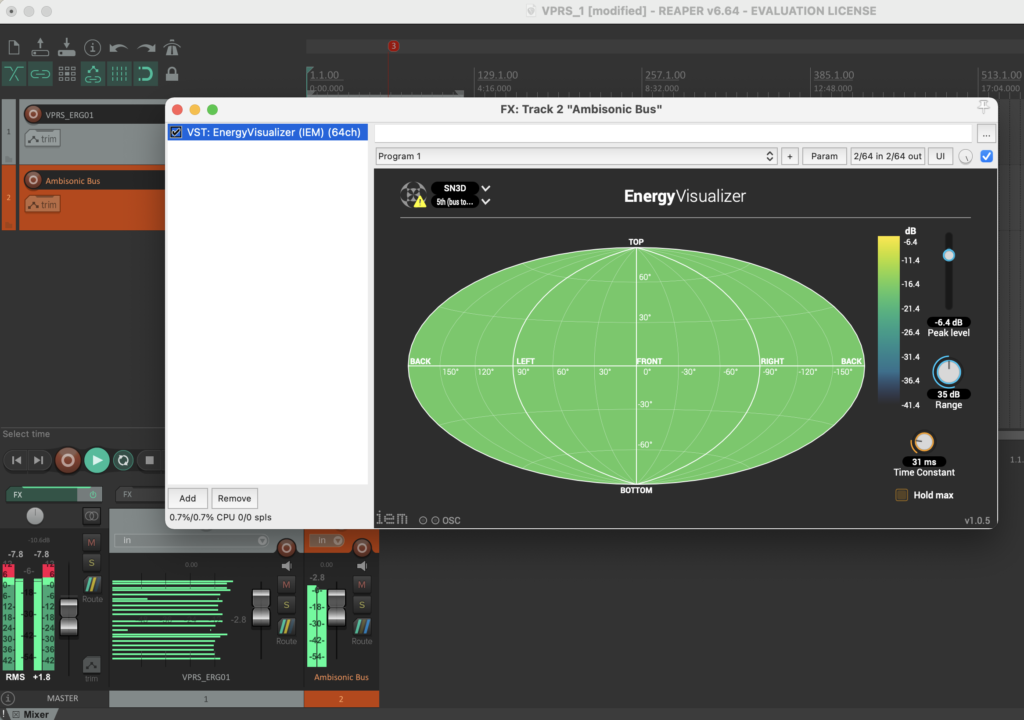

Finally, the note lists are combined with their respective rhythm tree in a voice object to form a voice, resulting in a total of three voices (R, G, B), which can then be combined in a poly object.

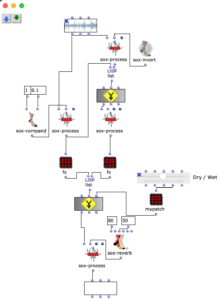

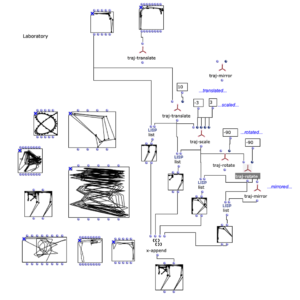

Image processing

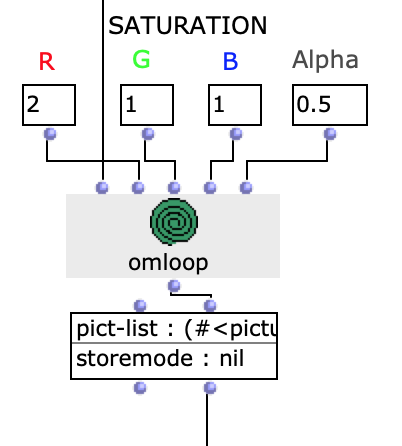

In order to additionally influence the sound result, it is possible to edit the saturation of the colour values of individual images of the selected sequence. The original images are then mixed with the altered ones.

Fig. 7: Changing colour values

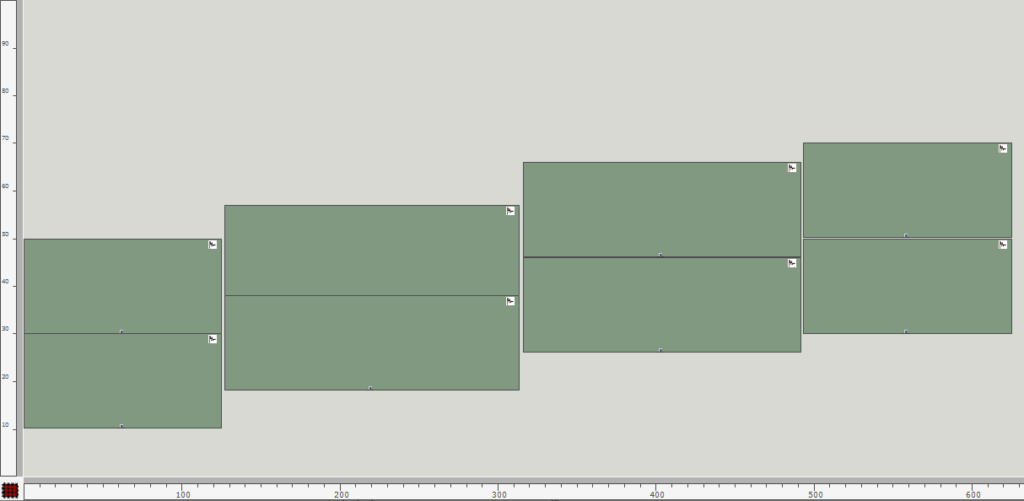

Example

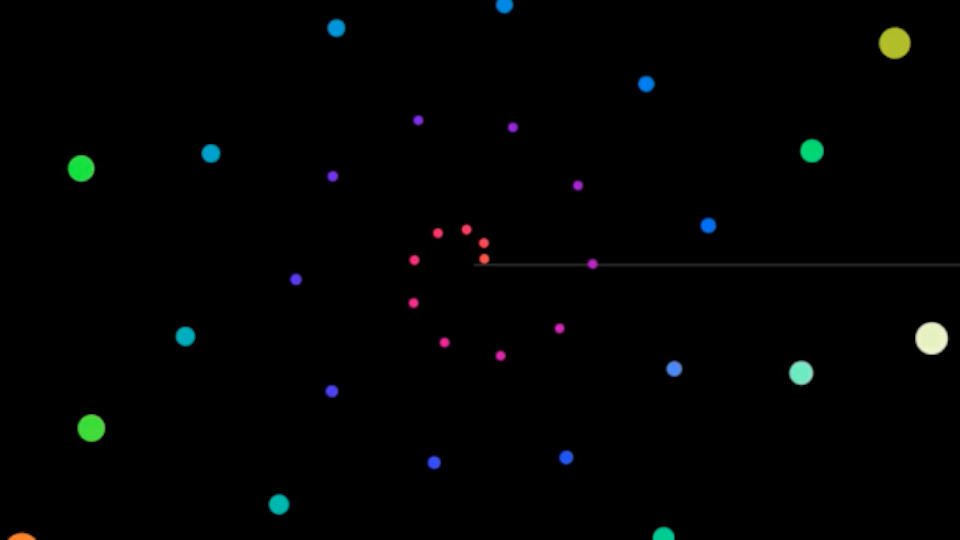

In the following, the frames of a video taken during a bus journey and showing the surroundings were used as the image sequence. Every thirtieth frame was saved. In the patch, the option of colour manipulation was also used to make the sequence a little more varied.

Fig. 8: Edited image sequence

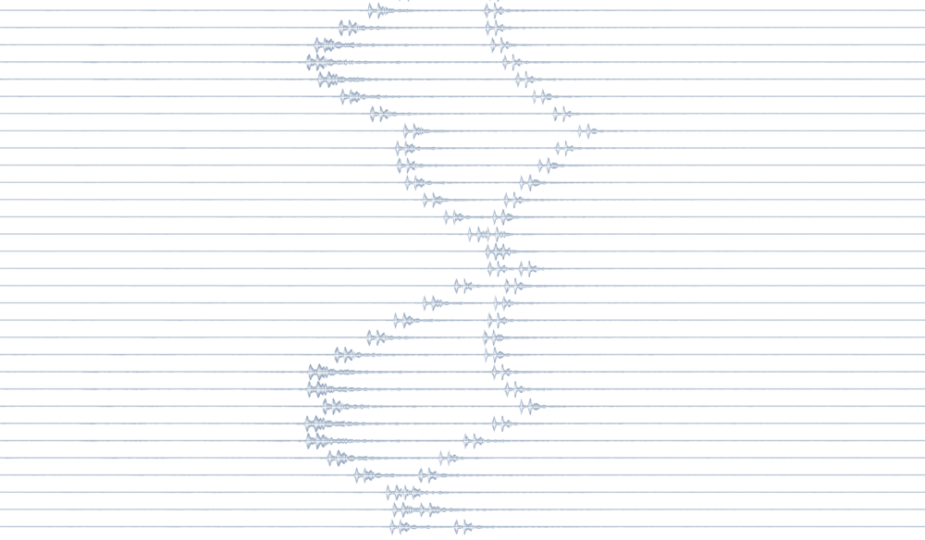

After evaluating the remaining patch, a possible end result of this image sequence could look and sound as follows:

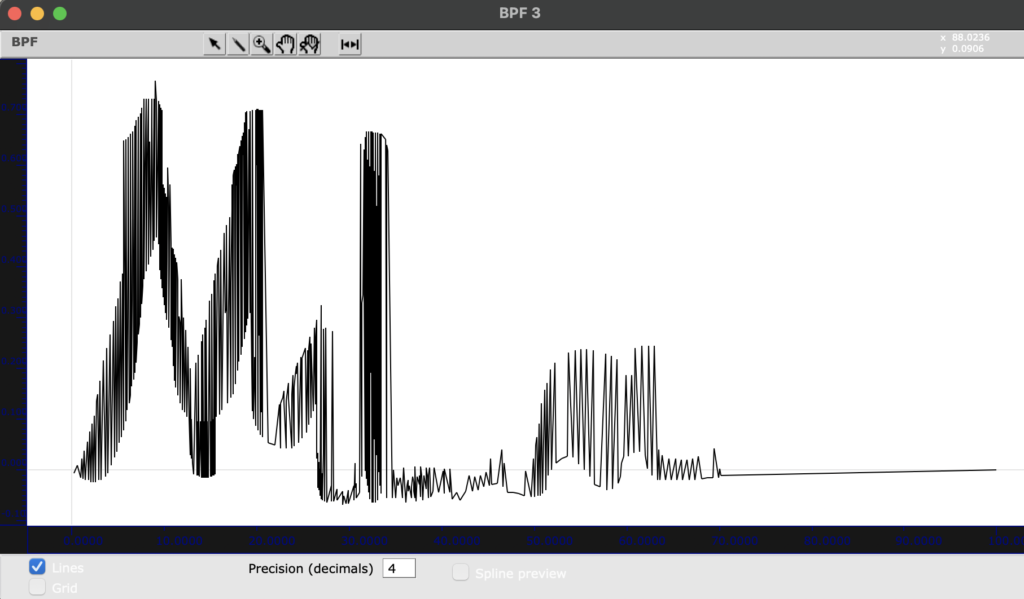

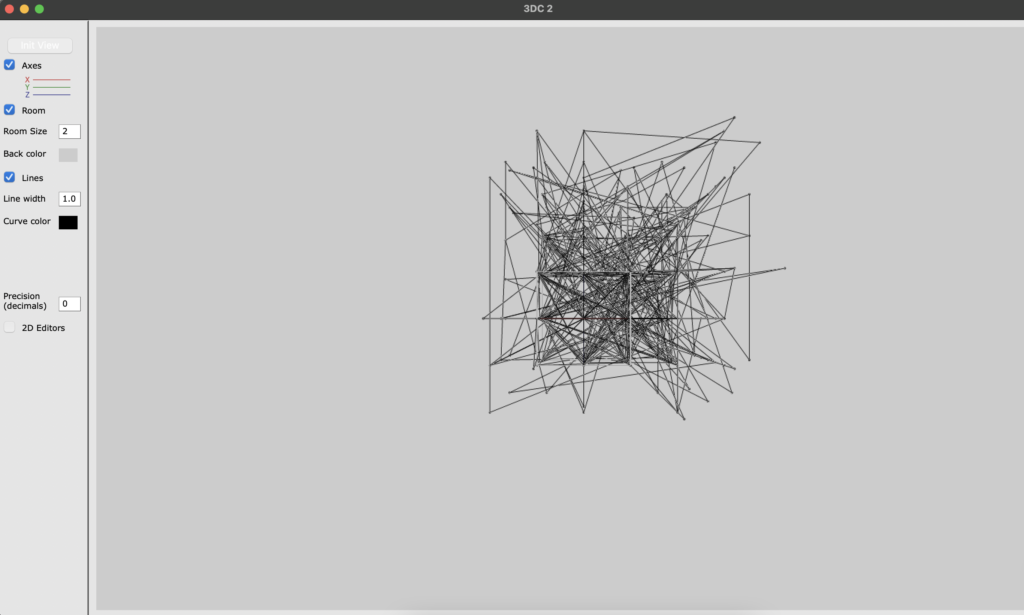

Fig. 9: Excerpt of symbolic representation